New Albany

New Albany

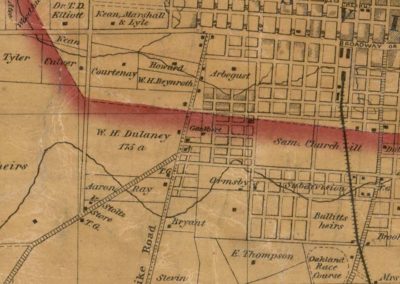

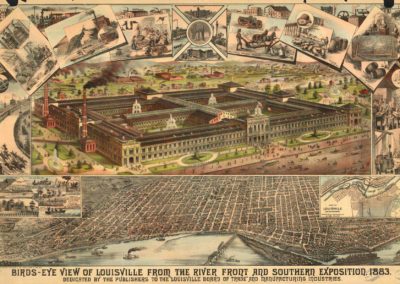

Located across the Ohio River, below the Falls of the Ohio, in southern Indiana. One of the six original settlements at the Falls of the Ohio which included Clarksville, Jeffersonville, Louisville, Portland and Shippingport.

The Scribner brothers arrived from New York in 1813 and named the town in honor of the capital of their home state. One of the Scribner houses, built c. 1814, is still standing at the southeast corner of Main and State Sts. The area became a transportation and ship building center.

Before the locks were completed on the Louisville side of the Ohio River in 1830, the river’s influence established New Albany as one of the largest cities in the midwest. The most lavishly furnished steam boats were built in New Albany. The first plate glass windows in the U.S. were produced here.

New Albany is significant for its excellent examples of 19th century commercial and residential architecture.

Mansion Row on E. Main St. is an outstanding collection of 19th and early-20th century architecture. Downtown contains a significant collection of commercial buildings, dating from the first half of the 1800s to the 1950s. A wide range of architectural styles are represented, including Federal, Greek Revival, Italianate, Renaissance Revival, Beaux Arts, Neoclassical and Chicago Commercial.

In addition to the Mansion Row several other neighborhoods in New Albany are on the National Register, they include Downtown, East Spring St., Cedar Bough, Shelby Place, DePauw Ave., Hedden’s Grove, and the Long-Graf House.

East Spring St. district is just east of the central business district and was a middle- to upper-class neighborhood. The Cedar Bough Place district is a short private street that runs between Ekin Ave. and Beeler St. and was considered one of the city’s most prestigious addresses. The Long-Graf House is a Queen Anne-style house at 1945 E. Elm St.

New Albany Historic Preservation Commission

New Albany – Floyd County Public Library