Seagrams Distillery

Seagrams Distillery

The most impressive of Louisville’s post-Prohibition distilleries was constructed between 1933 and 1936, and operated as the Kessler Distillery. When the distillery opened in May 1937, it was claimed to be the largest distillery in the world.

Their main product wasn’t bourbon, but high-proof neutral grain for ‘blended whiskeys’. The complex also produced industrial alcohol during World War II, for the production of synthetic rubber and medicines.

After Prohibition, many new distilleries were constructed in an area just southwest of Louisville known as St. Helens. Louisville wanted to annex the lucrative St. Helens area for tax revenue, but in 1938, the Kentucky General Assembly passed a bill requiring that at least 50% of the residents of an incorporated area approve annexation by a “Class 1” city (a definition which included only Louisville). Two months later, this area, including all of the distilleries in it, was incorporated as the city of Shively, ending Louisville’s annexation attempt.

The Seagram complex was designed by Louisville’s famed architectural firm Joseph & Joseph. The main office building is the Regency revival style. The Art deco brick warehouses were constructed in 1936, and included a system of underground tunnels, so that barrels could be moved around the complex without being seen by the public.

Seagram’s closed the distillery in 1983. Today, the main building is occupied by a charity, while the outlying buildings are multi-purpose use.

GALLERY

GALLERY

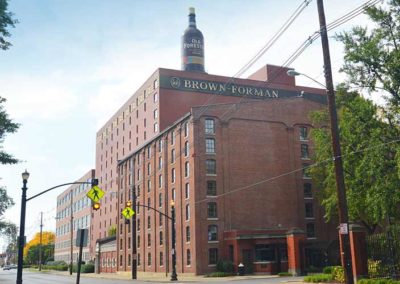

Brown-Forman Headquarters

Located between 19th & 20th Sts, and Howard & Garland Sts. Various distilleries operated here dating back to 1880, including Wallwork & Harris Distillery, White Mills Distilling Co., and the Lynndale Distillery. Brown-Forman bought the property in 1924, and in 1988 Warehouse A, built in 1936, was converted to offices.

Brown-Forman Co.

Built in 1881, the warehouse in the foreground was converted to offices in 1981. By 1988 all aging and distilling had been moved to the old Early Times Distillery further south on Dixie Hwy. in Shively.

Bernheim Distillery Bottling Plant

Bernheim Distillery Bottling Plant 822-828 S. 15th St., Moderne-style, c. 1925-1949