National Distillery

National Distillery

The first known commercial distillery in Jefferson County was built around 1860 by John Mattingly, on the banks of the Middle Fork Beargrass Creek, at Lexington Rd. & Gregory St.

Gregory St. was a block west of the intersection of Lexington Rd. & Payne St., on the north side of the street, the site of an apartment complex today.

This distillery was in a rural area surrounded by farmland, its neighbors were Cave Hill Cemetery (c.1848) to the south, and the Louisville and Frankfort railroad (c. 1850s) to the north.

By the 1880s, there were three large distilleries and eight warehouses, and by 1905, there were five distilleries located near the creek. Dozens of distilleries eventually became associated with the area over the years.

Other industrial complexes were built in the area, including livestock operations and the public workhouse. A mix of turn-of-the-twentieth-century housing developed around the industries and the area became known as Irish Hill.

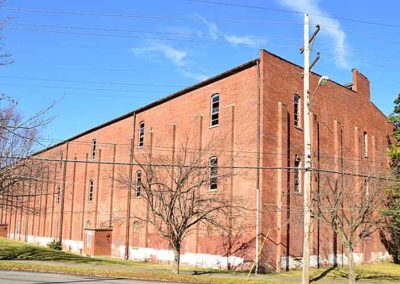

The oldest known bourbon warehouse structure in Louisville, the Williams Warehouse (c. 1880), is still standing at this location. The Central Warehouse (c. 1885) is connected to it on the right. A now-demolished third warehouse, to the left, created a large complex for aging and storage.

In the early 1890s, the Elk Run Distillery was the first to build on the south side of Lexington Rd. The largest warehouse ever built was located there, on Payne St. It was twelve stories tall, completed in 1918, and demolished for a school building in the 1980s. The Nelson Distillery Warehouse (c. 1896) is still standing at the corner of Lexington Rd. & Payne St.

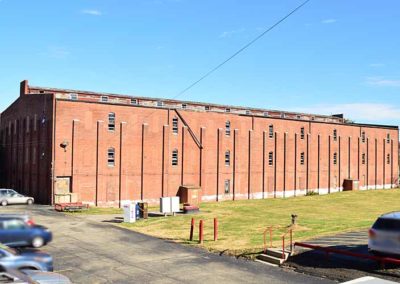

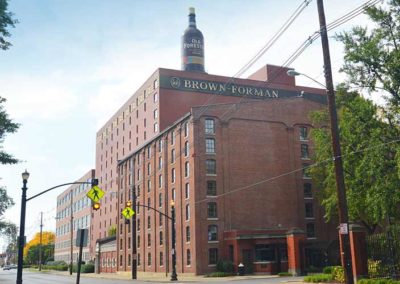

When Prohibition began in 1920 all of the distilleries were bought and used by the American Medicinal Spirits Co. By the time Prohibition had ended in 1933, all of the buildings had been purchased by National Distillers, and the complex was known as the Old Grand-Dad Distillery.

There was a history of distilling at this location for 154 years, until 1979, when National Distillers was acquired by Jim Beam. Today, the complex of buildings has a variety of uses and is known as Distillery Commons.